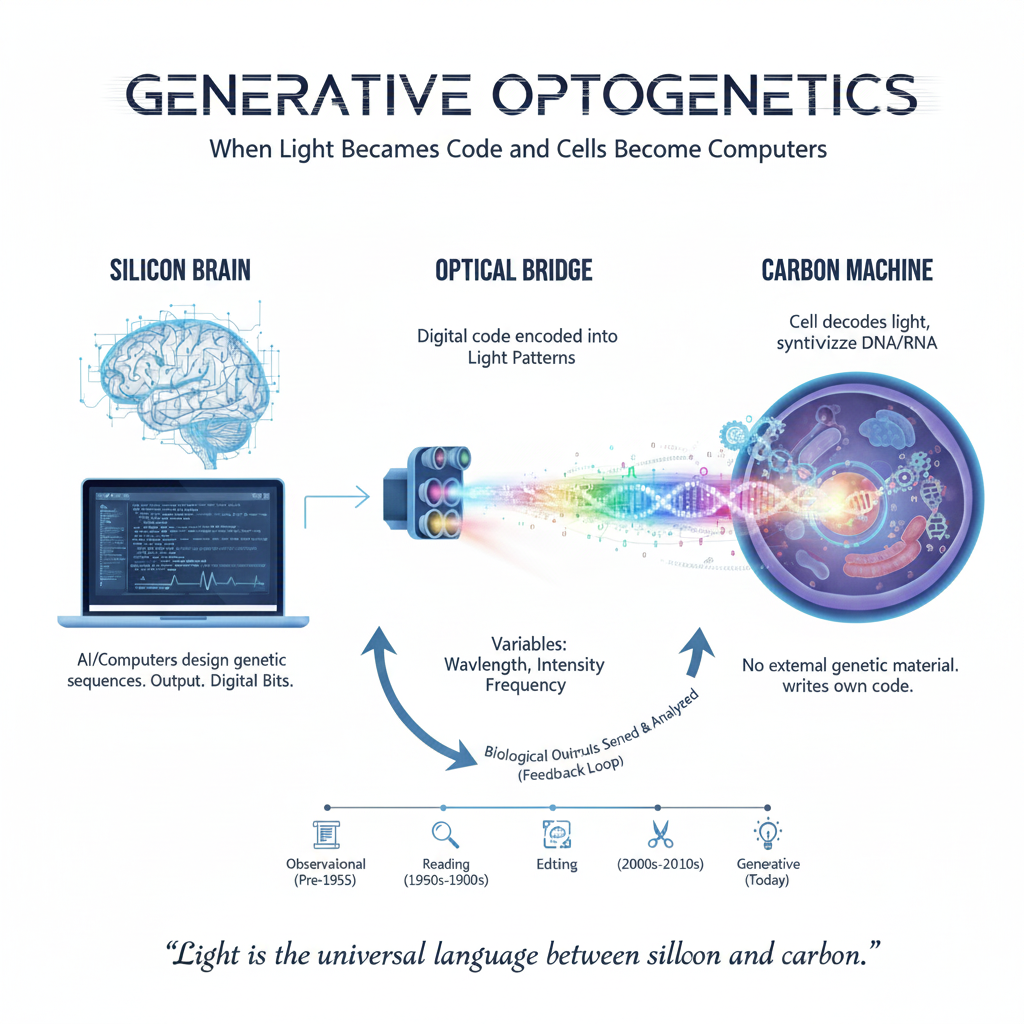

Generative Optogenetics: When Light Becomes Code and Cells Become Computers

DARPA has quietly launched what may be one of the most audacious bioengineering programs of the decade—and possibly of the century, called the Generative Optogenetics (GO), it fundamentally changes how humans interface with living systems. This is not just another gene-editing platform or a refinement of CRISPR that makes small changes to segments of the genome. It is an ambitious attempt to create molecular machines inside cells that can translate light directly into DNA and RNA sequences on demand.

In essence: shine specific wavelengths/frequency of visible or invisible light/energy at a living cell in-vitro or in-vivo, and the cell rewrites its own genetic instructions in real time. No viral vectors or external DNA delivery. Just photons triggering nucleotide incorporation using the cell’s own molecular machinery, something that even nature has yet to show us examples of. This is not incremental biology—it is a foundational shift in how information moves between silicon and carbon.

To understand why GO is so radical, we need to understand where biology has been, and why every previous approach hit structural limits.

From Observing Life to Controlling It on Command

For most of human history, biology was purely observational. We cataloged traits, diseases, and inheritance patterns without understanding the machinery underneath. The discovery of DNA’s structure in 1953 turned biology into an information science. Suddenly, life had a language, language that made sense of life itself.

Early researchers focused on reading and understanding genetic makeup —sequencing genomes, mapping genes, making sense of the regulatory networks. The early 21st century shifted toward editing: zinc-finger nucleases, TALENs, and eventually CRISPR-Cas systems allowed us to cut, insert, and modify genetic sequences with increasing precision.

But every gene-editing revolution shared the same hidden constraint: delivery.

Whether using viruses, lipid nanoparticles, electroporation, or microinjection, genetic engineering has always depended on massive external infrastructure—DNA synthesis facilities, cold chains, sterile transport, targeting mechanisms that degrade over distance and time. Biology could be edited, but only where logistics allowed, limiting the tools we have at our disposal. CRISPR made editing easier, it did not make biology programmable at scale.

Optogenetics: Teaching Cells to Listen to Light

Optogenetics, which emerged in the early 2000s, introduced a powerful idea: cells could be controlled with light. By engineering light-sensitive proteins (rhodoposins)—often derived from algae or bacteria—researchers learned to turn neurons on and off with millisecond precision using specific wavelengths. [1][2]

The foundational principle of optogenetics involves introducing light-sensitive proteins, primarily microbial opsins like channelrhodopsin, into target cells [4][8][9][10]. These genetically encoded proteins function as light-gated ion channels, pumps, or G protein-coupled receptors that undergo conformational changes upon illumination with specific wavelengths of light 911. For instance, channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2), derived from green algae, can be integrated into neuronal membranes, allowing neurons to be activated or silenced by pulses of blue or yellow light [4][12][13]. This precise control over cellular activity has transformed basic neuroscience research by enabling the manipulation and monitoring of specific neuronal circuits [8][11][4].

Optogenetics has evolved significantly since its inception, moving from its primary application in neuroscience to diverse biological systems and even non-excitable tissues [10][15][16]. Early applications focused on elucidating the causal relationships between neural activity and animal behavior in models like Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila [17][18][19]. Researchers have utilized optogenetics to manipulate various excitable cell types, including sensory neurons, interneurons, and motor neurons, to understand how neural circuits produce behavior 1718.

Generative Optogenetics asks a far more ambitious question: What if light didn’t just control cells—but wrote biological code inside them?

What DARPA’s Generative Optogenetics Is Aiming For?

DARPA GO is not about editing a gene here or activating a pathway there. It is about building intracellular molecular machinery that converts optical signals into sequence-specific DNA or RNA synthesis. Different wavelengths, intensities, durations, or temporal patterns of photons correspond to specific nucleotide incorporations. The cell itself performs the synthesis, guided by optically controlled molecular systems. Genetic information is transmitted without transmitting genetic material in real time.

A useful way to understand the magnitude of this shift is to think in terms of communication technologies rather than biology alone. This method could potentially offer unparalleled spatiotemporal resolution, enabling researchers to activate or inhibit cellular activity with millisecond precision [5][6][7].

Current genetic editing tools—CRISPR included—are best compared to a dial-up internet connection– slow, discrete, and burdened by overhead. Only limited amount of genetic material can be delivered at a time in a one-shot exchange of information and hope the gene edit lands at the intended location. The interaction is episodic, not continuous. Once the connection is made, you can’t dynamically change what’s being sent without starting the process all over again.

Generative optogenetics on the other hand looks far more like an optical fiber internet connection. Instead of physically shipping genetic instructions into cells, information is transmitted as light. The bandwidth jumps dramatically. Signals can be delivered continuously, in real time, and with fine-grained spatial and temporal precision. Different wavelengths, intensities, and pulse patterns act like multiplexed data streams, allowing multiple “messages” to be sent simultaneously or sequentially to the same biological system. Where CRISPR is a single file upload, optogenetics is a live data feed.

The difference is not just speed—it is interactivity. GO supports streaming, feedback, error correction, and dynamic routing. In biological terms, that means cells can receive instructions, respond, be observed, and then receive updated instructions moments later. Biology shifts from a batch-processed system to a real-time, networked one, opening the door to programmable biology at scale—where genetic information flows as easily as data, and living cells operate as responsive, addressable nodes in a biological network.

Today, computers design genetic sequences, but those designs must be physically instantiated elsewhere, shipped, delivered, and forced into cells. GO collapses that entire supply chain into a single step: optical transmission, however there are many steps in between that we don’t know about.

Why This Is a Foundational Shift

The implications go far beyond speed or convenience. GO fundamentally alters the interface layer between computation and biology. Researchers will need to think outside the box since there are no instructions set out by nature unlike CRISPR and others gene editing technologies copied from nature.

1. From Material Delivery to Information Transmission : Light is cheap, fast, scalable, and resilient. Genetic payloads are none of those things. GO replaces brittle logistics with pure information flow.

2. Single-Cell and Spatial Precision: Optics allow targeting at the level of individual cells or even subcellular regions. Different cells in the same tissue could receive different genetic instructions simultaneously.

3. Temporal Programming: Genes don’t just turn on—they turn on in sequence, on schedule, and in response to dynamic inputs. Biology becomes event-driven.

4. No Permanent Modifications: Instructions can be transient, reversible, or conditional. Cells don’t need to be permanently altered to be programmable.

This is not just gene editing. This is biological runtime execution.

The Wild Implications—If GO Works

DARPA explicitly positions GO as high-risk, high-reward. If it fails, it still advances foundational knowledge. If it succeeds, entire industries change.

Regenerative Medicine: Fixing damaged tissue illuminated with precise light patterns that cause cells to reprogram themselves in situ—differentiating, proliferating, repairing—without injections or implants.

On-Demand Biomanufacturing: Microbial cultures that synthesize complex molecules only when optically instructed. No fixed genetic circuits, no overproduction, no need for external production and injection. The cell themselves become bioprocessing units, leading to production of hormones, enzymes, etc whenever essential.

Personalized and Localized Medicine: Giving instructions to cells to manufacture drugs for particular diseases in exact locations instead of injecting/ingesting externally produced medicines.

Agriculture and Environmental Adaptation: Crops that dynamically alter gene expression—or even genetic structure—in response to environmental light signals. Adaptation becomes programmable rather than bred.

Spaceflight and Extreme Environments: In environments where supply chains break down—deep space, remote habitats, disaster zones—genetic instructions can be transmitted digitally and instantiated locally, saving time and energy. Bringing us another step closer to a space faring civilisation.

A Communication Protocol Between Life and Machines

What may be most profound about Generative Optogenetics is not any single application—but the abstraction it introduces. Imagine a bidirectional interface that lets AI design genetic sequences and encoding those sequences into living cells decode and execute them. The biological outputs are sensed, analyzed, and fed back into computation.

This is no longer “editing genes.” It is establishing a communication protocol between silicon and carbon, where light becomes the universal language.

Biology stops being something we manipulate externally and starts behaving like a programmable substrate—one that computes, adapts, and fabricates.

Why This Feels Like a Moonshot

DARPA moonshots are rarely incremental. They aim to create capabilities that don’t yet have markets because the markets depend on the capability existing first. GO sits in that tradition: risky and technically brutal. It requires breakthroughs in protein engineering, sequencing, photophysics, molecular biology, systems design simultaneously, nanotechnology perhaps and maybe we will get singularity before functional GO. But if it works, it unlocks programmable biology at a scale humanity has never had before. We aren’t even getting into the downsides of GO in this article since it will require a whole new blog.

Not faster editing. Not cheaper synthesis. Not better delivery. A new layer of reality — where genetic information moves at the speed of light, and living systems execute code designed in silico. This is the kind of moonshot that doesn’t just change a field. It changes what fields are possible at all.

References:

To, T. L., Cuadros, A. M., Shah, H., Hung, W. H. W., Li, Y., Kim, S. H., … & Mootha, V. K. (2019). A Compendium of Genetic Modifiers of Mitochondrial Dysfunction Reveals Intra-organelle Buffering. Cell, 179(5), 1205-1219.e23. 2

Schaeffer, J., & Belin, S. (2021). Standing By: How Intact Neurons React to Axon Injury. Neuron, 109(3), 395-397. 3

Xu, H., Dzhashiashvili, Y., Shah, A., Elbaz, B., Fei, Q., Zhuang, X., … & Ming, G. L. (2020). m6A mRNA Methylation Is Essential for Oligodendrocyte Maturation and CNS Myelination. Neuron, 105(1), 101-119.e6. 4

Chen, P., Lou, S., Huang, Z. H., Wang, Z., Shan, Q. H., Wang, Y., … & Zhou, J. N. (2020). Prefrontal Cortex Corticotropin-Releasing Factor Neurons Control Behavioral Style Selection under Challenging Situations. Neuron, 106(1), 154-169.e6. 5

Hirst, W. G., Biswas, A., Mahalingan, K. K., & Reber, S. (2020). Differences in Intrinsic Tubulin Dynamic Properties Contribute to Spindle Length Control in Xenopus Species. Current Biology, 30(12), 2243-2252.e4. 6

Steinmetz, N. A., Zatka-Haas, P., Carandini, M., & Harris, K. D. (2019). Distributed coding of choice, action and engagement across the mouse brain. Nature, 576(7786), 266-273. 7

Krueger, D., Izquierdo, E., Viswanathan, R., Hartmann, J., Cartes, C. P., & De Renzis, S. (2019). Principles and applications of optogenetics in developmental biology. Development, 146(20), dev175067. 8

Emiliani, V., Entcheva, E., Hedrich, R., Hegemann, P., Konrad, K. R., Lüscher, C., … & Yizhar, O. (2022). for light control of biological systems. Nature Reviews Methods Primers, 2(1), 1-27. 9

Byun, J. (2015). Optogenetics: a New Frontier for Cell Physiology Study. Journal of Life Science, 25(8), 953-956. 10

Sileo, L., Pisanello, M., Della Patria, A., Emhara, M. S., Pisanello, F., & De Vittorio, M. (2015). Optical fiber technologies for in-vivo light delivery and optogenetics. In 2015 17th International Conference on Transparent Optical Networks (ICTON) (pp. 1-4). IEEE. 11

Song, C., & Knöpfel, T. (2015). Optogenetics enlightens neuroscience drug discovery. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 14(12), 859-873. 12

Zhang, Q., Song, L., Fu, M., He, J., Yang, G., & Jiang, Z. (2024). Optogenetics in oral and craniofacial research. Journal of Zhejiang University-SCIENCE B, 25(8), 656-670. 13

Chen, S., Li, Y., Wang, Y., Chen, H., & Ozcan, A. (2025). Optical generative models. Nature, 632(8026), 758-765. 14

Wang, F. (2020). Optogenetics: The Key to Deciphering and Curing Neurological Diseases. Science Insights, 22(4), 310-315. 15

Guru, A., Post, R. J., Ho, Y. Y., & Warden, M. R. (2015). Making Sense of Optogenetics. The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 18(9), pyv079. 16

Tseng, H. A., Kohman, R. E., & Han, X. (2015). Optogenetics and electrophysiology. Oxford Medicine Online. 17

Ozawa, T. (2020). An Introduction to Optogenetics: Novel Tools for Physiological Psychology Research. Japanese Journal of Physiological Psychology and Psychophysiology, 38(1), 1-13. 18

Lüscher, C., Emiliani, V., Farahany, N., Gittis, A., Gradinaru, V., High, K. A., … & Deisseroth, K. (2025). Roadmap for direct and indirect translation of optogenetics into discoveries and therapies for humans. Nature Neuroscience, 28(11), 1809-1818. 19

Lan, T. H., He, L., Huang, Y., & Zhou, Y. (2022). Optogenetics for transcriptional programming and genetic engineering. Trends in Genetics, 38(12), 1251-1264. 20

Yang, F., Kim, S. J., Wu, X., Cui, H., Hahn, S. K., & Hong, G. (2023). Principles and applications of sono-optogenetics. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 194, 114674. 21

Yawo, H., Egawa, R., Hososhima, S., & Wen, L. (2015). General Description: Future Prospects of Optogenetics. In Optogenetics (pp. 95-103). Springer Japan. 22

Bregestovski, P. D., & Zefirov, A. L. (2019). Optogenetics and photopharmacology – effective tools for managing cell activity using light. Kazan medical journal, 100(6), 990-997. 23

Zhai, Y., Gao, F., Shi, S., Zhong, Q., Zhang, J., Fang, J., … & Li, S. (2025). Noninvasive Optogenetics Realized by iPSC-Derived Tentacled Carrier in Alzheimer’s Disease Treatment. Advanced Materials, 37(21), 2419768. 24

Banerjee, S., & Mitra, D. (2020). Structural Basis of Design and Engineering for Advanced Plant Optogenetics. Trends in Plant Science, 25(1), 1-4. 25

Inaba, M., Shikaya, Y., & Takahashi, Y. (2025). Optogenetics as a useful tool to control excitable and non-excitable tissues during chicken embryogenesis. Developmental Biology, 494, 148-154. 26

Chen, R., Gore, F., Nguyen, Q. A., Ramakrishnan, C., Patel, S., Kim, S. H., … & Deisseroth, K. (2020). Deep brain optogenetics without intracranial surgery. Nature Biotechnology, 38(11), 1243-1246. 27

Neghab, H. K., Soheilifar, M. H., Grusch, M., Ortega, M. M., Djavid, G. E., Saboury, A. A., & Goliaei, B. (2021). The state of the art of biomedical applications of optogenetics. Lasers in Surgery and Medicine, 53(8), 1011-1025. 28

Kushibiki, T. (2021). Current Topics of Optogenetics for Medical Applications Toward Therapy. In Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology (pp. 577-586). Springer Singapore. 29

Yamanaka, A. (2015). Neuroscientific Frontline of Optogenetics. In Optogenetics (pp. 195-207). Springer Japan. 30

Tan, P., He, L., Huang, Y., & Zhou, Y. (2022). Optophysiology: Illuminating cell physiology with optogenetics. Physiological Reviews, 102(4), 1639-1681. 31

Axelsen, T. M., Navntoft, C. A. E., Christiansen, S. H., Dreyer, J. K., Sørensen, J. B., Gether, U., & Woldbye, D. P. D. (2015). . Ugeskrift for Laeger, 177(11), 743-747. 32

Merlin, S., & Vidyasagar, T. (2023). Optogenetics in primate cortical networks. Frontiers in Neuroanatomy, 17, 1193949. 33

Pokala, N., & Glater, E. E. (2018). Using optogenetics to understand neuronal mechanisms underlying behavior in C. elegans. Journal of Undergraduate Neuroscience Education, 16(2), A152-A159. 34

Pedersen, N. P., & Gross, R. E. (2018). Neuromodulation Using Optogenetics and Related Technologies. In Neuromodulation Technology at the Neural Interface (pp. 647-662). Academic Press. 35

Li, W., Fan, B., Yong, K., & Weber, A. (2015). Microfabricated optoelectronic neural implants for optogenetics. In 2015 IEEE SENSORS (pp. 1-4). IEEE. 36

Kushibiki, T., & Ishihara, M. (2018). Application of Optogenetics in Gene Therapy. Current Gene Therapy, 18(2), 70-79. 37

Benisch, M., Aoki, S. K., & Khammash, M. (2023). Unlocking the potential of optogenetics in microbial applications. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 76, 102371. 38

Pierce, A. B., Pincus, A. B., Proskocil-Chen, B., Fryer, A., Jacoby, D. B., & Drake, M. G. (2023). Optogenetics Shines Light on Nerve-mediated Airway Hyperreactivity. C109. EVEN BETTER THAN THE REAL THING: ADVANCED MODELS OF LUNG DISEASE, A2694-A2694. 39

Fang-Yen, C., Alkema, M. J., & Samuel, A. D. T. (2015). Illuminating neural circuits and behaviour in Caenorhabditis elegans with optogenetics. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 370(1678), 20140212. 40

Morton, A., Murawski, C., & Gather, M. C. (2016). Carpe lucem: harnessing organic light sources for optogenetics. The Biochemist, 38(6), 4-9. 41

Berry, R., Getzin, M., Gjesteby, L., & Wang, G. (2015). X-optogenetics and U-optogenetics: Feasibility and Possibilities. Photonics, 2(1), 23-33. 42

Jiang, C., Li, H. T., Zhou, Y. M., Wang, X., Wang, L., & Liu, Z. Q. (2017). Cardiac optogenetics: a novel approach to cardiovascular disease therapy. EP Europace, 20(9), 1435-1442. 43

Montagni, E., Resta, F., Mascaro, A. L. A., & Pavone, F. S. (2019). Optogenetics in Brain Research: From a Strategy to Investigate Physiological Function to a Therapeutic Tool. Photonics, 6(3), 92. 44

Park, K. H., & Kim, K. W. (2025). Optogenetics to Biomolecular Phase Separation in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Molecules and Cells, 48(3), 195-202. 45

Ren, H., Cheng, Y., Wen, G., Wang, J., & Zhou, M. (2023). Emerging optogenetics technologies in biomedical applications. Smart Medicine, 2(1), e70. 46

Riemensperger, T., Kittel, R. J., & Fiala, A. (2016). Optogenetics in Drosophila Neuroscience. In Methods in Molecular Biology (pp. 209-224). Humana Press, New York, NY. 47

Zhou, Y., Ding, M., Duan, X., Konrad, K. R., Nagel, G., & Gao, S. (2021). Extending the Anion -Based Toolbox for Plant Optogenetics. Membranes, 11(4), 287. 48

Lin, Y., Yao, Y., Zhang, W., Fang, Q., Zhang, L., Zhang, Y., & Xu, Y. (2021). Applications of upconversion nanoparticles in cellular optogenetics. Acta Biomaterialia, 133, 46-56. 49

Zhang, H., Fang, H., Liu, D., Zhang, Y., Adu-Amankwaah, J., Yuan, J., … & Zhu, J. (2022). Applications and challenges of rhodopsin-based optogenetics in biomedicine. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 16, 966772. 50